2. CONTEXT OF MINERALS AND WASTE DEVELOPMENT IN NORTHAMPTONSHIRE

Policy context

The Local Plan has to be prepared within the wider strategic policy context, this is set out at the national and european level (including legislation, directives and planning policy, in particular the NPPF1 as well as the local level (in particular the Sustainable Community Strategy).

1 The majority of Planning Policy Statements (PPSs), Minerals Planning Guidance (MPGs) and Minerals Policy Statements (MPSs) were cancelled with the publication of the NPPF. However, a number of minerals and waste documents have been retained, these will remain in force until such time as they are cancelled or replaced.

Minerals policy context

The NPPF sets out the broader context, key objectives and considerations for minerals planning. The NPPF requires each Minerals Planning Authority (MPA) to prepare an annual Local Aggregate Assessment (LAA) based on a rolling average of ten years sales data, other relevant local information and an assessment of all supply options. In doing so the MPA should take account of the advice of relevant Aggregate Working Party(ies) (AWPs) and the National Aggregate Co-ordinating Group as appropriate. The LAA provides the basis for identifying the plans aggregate provision rates. In planning for a steady and adequate supply of aggregates the NPPF recommends landbanks of at least seven years for sand and gravel and ten years for crushed rock.

Waste policy context

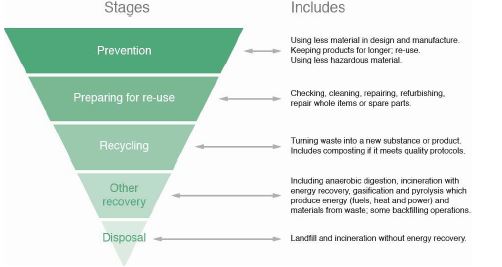

Key elements of the European policy context for waste include the Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC) and Landfill Directive (99/31/EEC). The Waste Framework Directive sets out the concept of the waste hierarchy, proximity principle and self-sufficiency. It also requires that waste is recovered or disposed of without endangering human health or causing harm to the environment. The Landfill Directive aims to prevent or reduce as far as possible negative effects on the environment from the landfilling of waste, and setting targets for the reduction of biodegradable municipal waste going to landfill. A number of other European Directives also influence waste management processes in the UK and are aimed at targeting specific sectors, including the Incineration Directive, Packaging Waste Directive, Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Directive and End of Life Vehicles Directive.

The national policy context is primarily set out through the Waste Regulations 2011, which transposes the Waste Framework Directive to UK law and national planning policy. The Waste Management Plan for England sets out the high level strategy for supporting the implementation of the objectives and provisions of the Waste Framework Directive. Although the NPPF influences the context of waste planning it does not specifically address waste matters. Detailed waste planning policy is set out in the National Planning Policy for Waste (NPPW). The NPPW is to be read in conjunction with the NPPF, Waste Management Plan for England and National Policy Statements (NPS) for waste water and hazardous waste. There have been considerable policy changes recently, including the end of the Landfill Allowance and Trading Scheme (LATS) after the 2012/3 scheme year in England. LATS was no longer considered to be the major driver for diverting waste. The landfill tax escalator is a more effective incentive for local authorities to reduce the waste they send to landfill. However, the aim of moving waste disposal up the waste hierarchy (shown in Figure 1) remains a key element.

National policy context regarding radioactive waste is set out through a number of documents, those of specific relevance to Northamptonshire’s local circumstance address low level radioactive waste, including the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA) Strategy (Strategy III) (April 2016), Policy for the Long Term Management of Solid Low Level Radioactive Waste in the United Kingdom (2007) and the UK Strategy for the Management of Solid Low Level Radioactive Waste from the Nuclear Industry (2016).

At a local level, the Northamptonshire Joint Municipal Waste Management Strategy (JMWMS) sets out the County’s aims, objectives and targets for the management of municipal waste. The JMWMS sets out how the councils in Northamptonshire will manage the collection and treatment of municipal waste and identifies the types of services and technologies needed to reach the partnership’s goals2

2 The cancellation of LATS along with the revised procurement process has led to a review of the JMWMS model; however, the changes have not been substantial. In addition the cancellation of the private finance initiative (PFI) credits scheme ‘Project Reduce’ also lead to changes to the Councils procurement process for residual waste treatment contracts. There will be three new contracts for the treatment and disposal of residual municipal waste commencing 1st April 2013 (with a duration of seven years and an option to extend by up to five years). All of the contracts include Mechanical Biological Treatment (MBT); with one generating a Refuse Derived Fuel (RDF) that will be used in an advanced thermal treatment power generating system, and another generating a solid recovered fuel that will be used by the cement industry. Collectively, the contracts will divert in excess of 65% of residual municipal waste from landfill.

Figure 1: Waste hierarchy

Waste management and disposal targets

Targets for waste management and disposal set through the policy hierarchy are summarised below.

Landfill Directive

- Reduce the proportion of biodegradable municipal waste sent to landfill to 50% of 1995 levels by 2013 and 35% by 2020.

Waste Strategy for England

- Reduce the amount of household waste not re-used, recycled or composted from over 22.2 Million tonnes (Mt) in 2000 by 35% in 2015 with an aspiration to reduce it to 12.2 Mt in 2020 (a reduction of 45%).

- Increased recycling and composting of household waste to at least 45% by 2015 and 50% by 2020.

- Increased recovery of municipal waste of 67% by 2015 and 75% by 2020.

Northamptonshire Joint Municipal Waste Management Strategy3

- Household waste recycling (including composting) rate of 48% by 2012/3, 52% by 2015/6 and 56% by 2019/20.

- Meet the annual landfill allowances required in the Waste and Emissions Trading Act 2003.

3The JMWMS incorporates EU and National targets for household and municipal waste. As such it is only necessary to address these in the report and models. Please refer to the JMWMS for full details.

The Sustainable Community Strategy

The Local Plan is part of the development plan system but it has an important inter-relationship with the Northamptonshire Sustainable Community Strategy (SCS). The SCS is a partnership document prepared following consultation with local communities and key local partners through the Local Strategic Partnership (LSP), but led by the local authority. The SCS replaces Community Strategies, and in the case of a two tier local authority area, such as Northamptonshire, the county-wide strategy becomes the overarching strategy with which district level strategies must dovetail.

The inter-relationship is such that the SCS has to take full account of spatial, economic, social and environmental issues, many of which are set out and articulated in the county’s Local Plan; whilst the key spatial planning objectives for the area as set out in the Local Plan are fully aligned with SCS priorities.

The SCS for Northamptonshire was approved in October 2008. It contains four ambitions for Northamptonshire:

- Ambition 1: To be successful through sustainable growth and regeneration.

- Ambition 2: To develop through having a growing economy and more skilled jobs.

- Ambition 3: To have safe and strong communities.

- Ambition 4: Healthy people who enjoy a good quality of life.

A number of aspirations are identified under each theme. For the Local Plan the first ambition, ‘to be successful through sustainable growth and regeneration’ is the most relevant. This ambition contains three aspirations that link between the Local Plan and the SCS.

A number of aspirations are identified under each theme. For the Local Plan the first ambition, ‘to be successful through sustainable growth and regeneration’ is the most relevant. This ambition contains three aspirations that link between the Local Plan and the SCS.

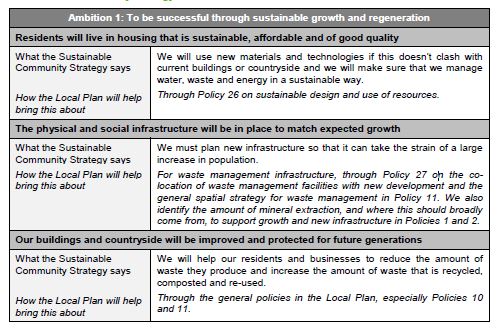

The manner in which the Local Plan will seek to meet these aspirations is set out in Table 1 below.

Table 1: How the Local Plan supports the ambitions and aspirations of the Northamptonshire Sustainable Community Strategy

Strategic planning context

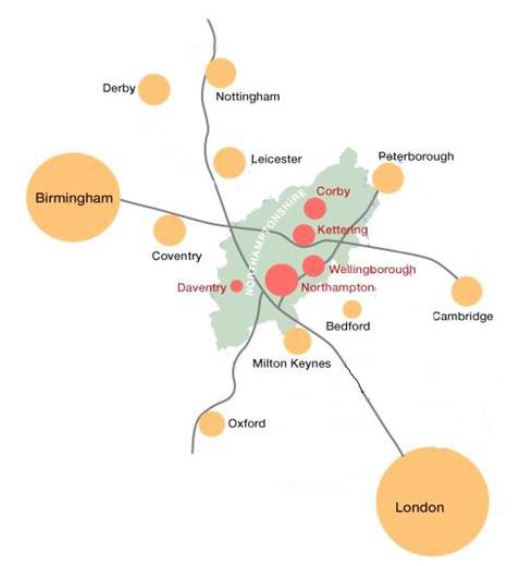

Northamptonshire is a county at the heart of England, but has no particular alignment to any region. It has traditionally been ‘officially’ part of the East Midlands region, which includes Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire, yet Birmingham is the nearest major regional city to the county. There is also a strong affinity with the South East and East of England. Although east-west road links are good the key transport communication links, and therefore other links, are with the world city of London. Taken together the closeness of the relationships with the east, south-east and London make Northamptonshire effectively a part of the wider south-east functional area.

Plan 1: Northamptonshire in its wider context

Northamptonshire and growth and development

Planning for minerals and waste related development needs to reflect Northamptonshire’s regional context, but also fundamentally requires to be linked to the wider development picture. This is one that sees Northamptonshire continuing as an important area for growth and development.

The broad development strategy for Northamptonshire comes forward through the plans prepared by the county’s Local Planning Authorities (LPAs).

Within the County development will generally be concentrated in two main areas: Northampton and Corby / Kettering / Wellingborough, with a secondary focus at Daventry (in other words five of the current six main population centres), but there will also be some development at Towcester and Rothwell / Desborough. There will be more local development at the remaining towns and a very small number of other settlements. The exact location of this development and the identification of the other settlements are set out in jointly created plans, produced for the west and the north of the county by the West and North Northamptonshire Joint Planning Units which cover all development planning matters except for minerals and waste development. Whilst the County is split for development and growth management purposes, it is recognised that Northamptonshire does not functionally operate as distinct northern and western areas, and that it is important to develop economic and planning proposals that can form a coherent whole, especially for minerals and waste matters.

The scale and location of growth within the county will emphasise that the population focus for Northamptonshire will be very much along the Northampton - Wellingborough / Rushden - Kettering - Corby axis. Population and job growth has implications for both minerals and waste development. Minerals and waste facilities will be required to support development (through the supply of building materials and handling of waste from construction) and throughout the community’s life (e.g. provision of waste management facilities).

Planning for minerals and waste should therefore seek to ensure the provision of an adequate and steady supply of minerals and the development of a sustainable waste management network. The approach to mineral extraction and waste management (and where necessary disposal) in this county is guided at a strategic level by national guidance but also should acknowledge the growth and development strategies set out in the plans prepared by the county’s LPAs.

Economy and jobs

Whilst Northamptonshire is relatively self-contained in employment terms, its labour markets are linked to those of surrounding areas and its businesses function within national and international supply chains. However there are growing flows of people to destinations elsewhere such as Milton Keynes, Cambridge and London. Significant housing growth should ideally be matched with commensurate economic development, otherwise people will increasingly live in Northamptonshire and work elsewhere. Already the labour market pull of the larger towns in Northamptonshire, and particularly Northampton itself, is not as strong as could be expected.

Northamptonshire has maintained a relatively strong economy; in terms of Gross Value Added (GVA) per head, the county performs above national averages. It should also be borne in mind that GVA is highest in urban authorities compared to rural ones; Northamptonshire under this measure is a rural authority area. Its high GVA is therefore a good performance. The high GVA per head performance derives from the high levels of employment; Northamptonshire has economic activity rates approaching 81.9% and an employment rate of 76.5% (4.3% of the population are economically inactive but seeking employment). On average those that are working in the county are in relatively low value jobs, however average earnings are higher than the East Midlands average.

The concentration of businesses and levels of entrepreneurship per capita is generally higher in the rural areas of South Northamptonshire, Daventry and East Northamptonshire, with lower concentrations in Corby and Northampton.

Although classed as being economic development, minerals and waste related development has a very limited role to play in addressing the structural issues highlighted above compared to other elements of planning and development. Waste development has the greater role of the two, particularly as new technologies for waste management come forward and the industry moves from being a predominantly low value, low skilled sector into a more balanced one. Waste management is a key part of the Environmental Technologies job sector, along with renewable energy, and this job sector is one that Northamptonshire’s economic agencies consider should be supported to grow in the county, particularly in North Northamptonshire.

Historically there has been a tendency to dispose of waste (with the emphasis very much on disposal rather than treatment) in former mineral workings. As most of these workings were located in rural areas the majority of waste was not disposed of, let alone treated, close to where it was generated. The strong move away from waste disposal to treatment, coupled with advancements in waste technologies and design, has resulted in waste management facilities being able to be co-located with other forms of development (i.e. no longer rural-centred). They can therefore be better linked to where waste is actually generated.

Locations for mineral extraction in Northamptonshire

Mineral deposits suitable for use as aggregates are not evenly distributed and as such there are often geographical imbalances between where the demand for aggregates arises and the location of the resources which can meet those demands. This can often result in the need to import and export a proportion of a particular mineral requirement from / to other sub-regions or regions. As far as is practical however, minerals should be sourced indigenously; as required by national policy. This will help to mininise the transportation of minerals and support local markets.

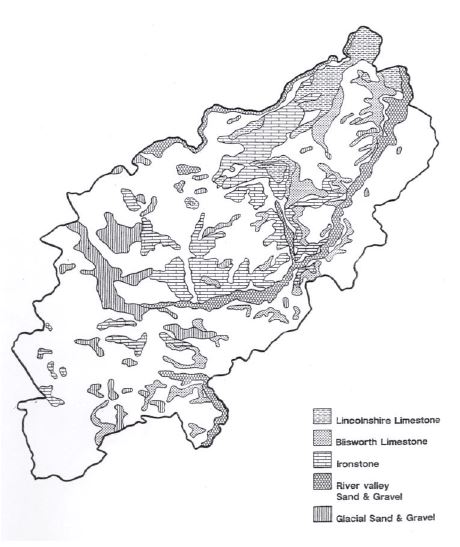

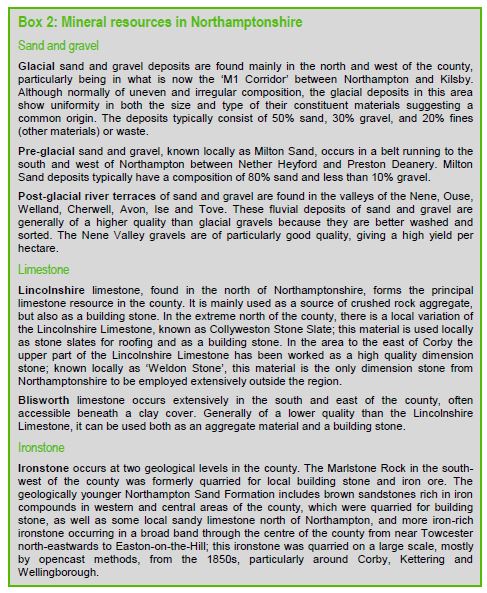

The main resources present in Northamptonshire are sand and gravel, limestone and ironstone. Historically, in terms of economic value, sand and gravel is the most important mineral resource found in the county. Recently however trends for growing limestone sales highlight the potential demand for limestone to outweigh that of sand and gravel in the future.

Within the county there are three main types of sand and gravel deposits: glacial and pre-glacial which are found in the north-west and south-central parts of the county, and post-glacial which are present in river valleys across Northamptonshire. Limestone (crushed rock) is primarily found in the north and north-east of the county. Ironstone deposits are also found in large parts of central and east Northamptonshire but have minimal economic importance and are no longer extracted.

In the twenty years prior to 2011 sand and gravel extraction in Northamptonshire has been focused in the Nene Valley between Northampton and Stanwick, with extraction from a number of small sites elsewhere in the county including the Milton Sands area to the south-east and south-west of Northampton, and at one site in the Great Ouse Valley. Crushed rock extraction has been focused to the north and north-west of Northampton and at one site in the north-east of the county.

Soft sand production in the recent years up to the beginning of the Local Plan period has been concentrated at a site to the south-west of Northampton in the Milton Sands belt, where working has now ceased. It is becoming increasingly difficult to identify new sites for soft sand extraction in the county. As there is no specific requirement to have a specific soft sand provision rate, it is considered to be appropriate in the Northamptonshire context to have a general sand and gravel provision rate which does not separate out soft sand.

Whether extraction should be from the river valley or glacial areas has been a key issue in respect of mineral extraction in the county in the recent past and had led to a policy stance, set out in the Minerals Local Plan 1997 and its 2006 review, to move away from river valley extraction to more upland (glacial) areas of Northamptonshire.

This stance was largely driven by landscape and restoration issues. The concerns were that past extraction from the Nene Valley and its restoration to lakes had adversely altered the landscape character, and that further extraction in river valleys would continue to do so. It was considered that there would not be the same impact on overall landscape character if extraction took place in the glacial areas.

Plan 2: Geological map of the chief mineral resources of Northamptonshire

However, the view that the impact of extraction and restoration in glacial areas would not be as marked as in the river valleys, is complicated by the fact that landscape and other impacts in the pre-glacial, and in particular the glacial areas, can be as significant in their own way in landscape terms (if not landscape character terms). As such there would need to be either restoration to agriculture through bringing in replacement fill or alternatively for the land to be re-shaped following extraction.

Furthermore restoration of extracted sites in river valleys to lakes would now no longer be pursued even if extraction was permitted, and restoration to a mix of agriculture and wetland habitats would instead occur. This would involve bringing in replacement fill as would be the case for the glacial sites. It should also be noted that river valley restoration is seen to be more conducive to increasing biodiversity.

When the move away from river valleys was first set out in policy in the mid 1990s, the view was that the glacial areas, when added to supplies from the pre-glacial areas, would provide a reasonable alternative supply of minerals to the river valleys. However, glacial deposits for potential extraction have not been put forward by the minerals industry, let alone worked, because the quality of resources is variable therefore reducing the economic viability of extraction. It is also now acknowledged by geologists that the resources in the glacial areas are far more limited in extent than originally envisaged.

This has therefore moved the agenda from being simply a landscape issue, to also one of needing to ensure the supply of quality sand and gravel in a growing county. Where extraction is currently taking place such as the central Nene Valley or the Great Ouse, rather than valleys such as the Ise where there is no history of extraction, then extraction would be focused in these locations together with extraction from glacial and pre-glacial areas.

Catchment areas for waste management and disposal

The Local Plan seeks to provide waste management and disposal capacity equivalent to meet the County’s own needs, i.e. net self-sufficiency. There is no requirement for Northamptonshire to take a proportion of London’s waste. Although London is seen to have considerable difficulties in being self-sufficient in its ability to deal with the waste it generates this does not mean that it should not endeavour to take responsibility for the waste produced by its community.

Northamptonshire is a net importer of waste, by applying a catchment area approach we recognise that although cross boundary movements do occur the preference is to keep these to a minimum or achieve a mass balance; this is primarily for reasons of sustainability. There will inevitably be some cross-border flows for reasons of geographical convenience, which may be broadly balanced. This may occur due to some waste management facilities (both within and outside the County) requiring a wider catchment area as a result of operational requirements and treatment processes or the specific waste stream.

This approach also means that we should be able to better plan for sustainable waste management and disposal in the county as we are more aware of waste movements and, coupled with our goal of achieving net self-sufficiency, means that we do not need to specifically provide for another area’s waste generation.

The Local Plan recognises that waste management is becoming more specialised and is also a higher value industry than previously. It is not appropriate to oppose facilities serving wider catchments when other industries and commercial enterprises are not so constrained. However, in the wider interests of sustainability, it is not envisaged that Northamptonshire should take on a role as a key sub-national location for waste management or disposal facilities.